Saturday, February 17, 2018

Friday, February 16, 2018

Black Panther and Afrofuturisim

What The Heck Is Afrofuturism?

Guest Writer

ILLUSTRATION: GABRIELA LANDAZURI/ HUFFPOST IMAGES: GETTY IMAGES WALT DISNEY PICTURES

Many of us blerds (black nerds, to you) who have read the Black Panther comics

never thought the day would come when we would finally see this story adapted for the

big screen. With the movie’s already profound effect on pop culture, it is provoking

deeper discussions around reimagined worlds with black politicians, spiritual

leaders and monarchs at the helm. We’re hearing the word “Afrofuturism” a lot.

But what exactly is Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism is the reimagining of a future filled with arts, science and technology

seen through a black lens. The term was conceived a quarter-century ago by white author Mark Dery in his essay “Black to the Future,” which looks at speculative

fiction within the African diaspora. The essay rests on a series of interviews with

black content creators.

Dery laid out the questions driving the philosophy of Afrofuturism:

Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces

of its history, imagine possible futures? Furthermore, isn’t the unreal estate of

the future already owned by the technocrats, futurologists, streamliners, and

set designers ― white to a man ― who have engineered our collective fantasies?

What makes Afrofuturism significantly different from standard science fiction is

that it’s steeped in ancient African traditions and black identity. A narrative that

simply

features a black character in a futuristic world is not enough. To be Afrofuturism,

it must be

rooted in and unapologetically celebrate the uniqueness and innovation of black

culture.

The biggest proponent of this cultural movement, even before it had its name, was musician Sun Ra, who infused elements of space and jazz fusion in his work as a musical artist. Prolific science fiction author Octavia E. Butler explored black

women protagonists in novels like Fledging, Dawn, Parable of the Sower and

Lilith’s Brood, set in the context of futuristic technology and interactions with the supernatural. In the contemporary music world, singers like Erykah Badu, with her eccentric and experimental imagery in videos and album covers, promote the intersection of art

and futurism. Artists like Janelle Monae, with her android alter-ego and electronica sounds, and films like “Brown Girl Begins,” a post-apocalyptic tale set in 2049 and directed by Sharon Lewis, pay a huge homage to Afrofuturism.

WALT DISNEY STUDIOS

Subscribe to The Morning Email.

Wake up to the day's most important news.

Then there’s “Black Panther.” The film wears themes of Afrofuturism proudly on its sleeve. Tech genius Princess Shuri is not only the smartest person in the fictional

world, but she’s responsible for the creation and maintenance of sophisticated

gadgets

for her brother T’Challa, a.k.a. Black Panther.

A prosperous alternative afro future can be seen in their fictional East African

home of Wakanda, a small country the size of New Jersey that has never been colonized

and is steeped in its blackness. It’s a utopian society that also boasts one of the

world’s

richest resources, vibranium. Because white supremacy never intruded on

Wakandan

culture and its people, ancient African traditions remain common practice there.

But this movie is more than just a glorious film ― it’s the expression of a movement.

Black Panther is a superhero who is for us by us. We can claim him.

Africans and African-Americans have full autonomy as Afrofuturists. A community

of people can take a piece of visual art or notes from a song and develop an entire universe and say, “This is ours.” And that’s what this film represents to so many

excited fans. Black Panther is a superhero who is for us by us. We can claim him.

In addition to the predominantly black cast filled with Hollywood stars and starlets, “Black Panther” also had a black production team spearheading the

shaping of this story. The writer, filmmaker and executive producer are African-American. Production designer Hannah Beachler, who was influenced by

Afrofuturistic architecture and Afropunk aesthetics, helped lay the groundwork

for this world. The African regalia and elaborate costumes by famed wardrobe

designer Ruth E. Carter created a Wakandan couture that would give New York

Fashion Week a run for its money ―

just look at her use of kimoyo beads as both a fashion accessory and a

communication device.

This intersection of sci-fi and African pride is what we’ve come to know as Afrofuturism. For many of us in the blerd community, the film with its love for

technology, science, visual art and music (if you haven’t checked out the “Black Panther” album, you should make it a priority) is what we’ve been hungry for.

I hope, for all of our sakes, that this is also just the beginning. I hope that “Black Panther” can prove that stories permeated in blackness have crossover appeal.

I hope we get more and more stories of black people who have agency, who are

free and subservient to no one. Black people deserve to see themselves leading

the way in real or abstract futures.

Jamie Broadnax is the editor-in-chief and creator of the online community for

black women called Black Girl Nerds.

Thursday, February 15, 2018

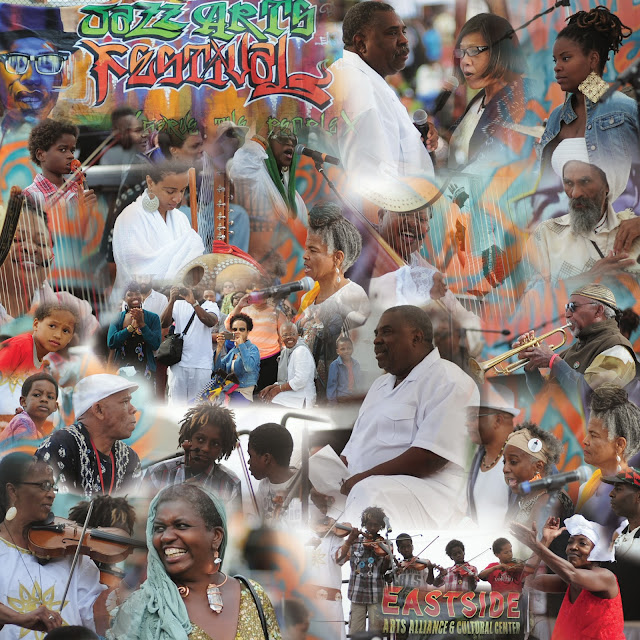

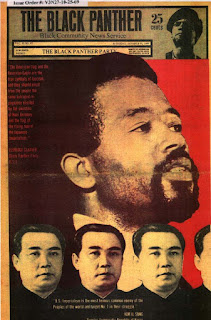

Marvin X--the revolutionary who never came in from the cold

"And it is gratifying in an era of the sellout, faint hearted and fallen, to see that Marvin X was one black man who met the white man in the center of the ring and walked with him to the corners of psycho-social inequity, grappling with him through the bowels of the earth, yet remained one black man the white man couldn't get."--Dr. Nathan Hare

Marvin X--the revolutionary who never came in from the cold

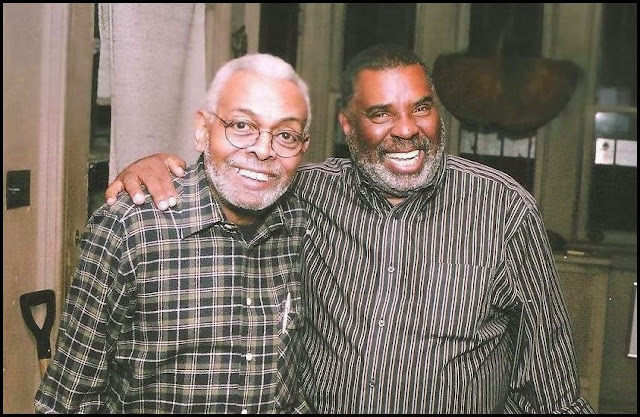

AB and MX, 47 years of revolutionary work and friendship

Askia Toure', co-founder of BAM. Gave Marvin X his first tour of Harlem, NY, when MX arrived underground, with the FBI on his heels for refusing to fight in Vietnam. Marvin X arrived in Harlem just in time to kick off the Black Arts Movement, along with Baraka, Askia, Larry Neal, Sonia, Nikki, Haki, Last Poets, Barbara Ann Teer, Sun Ra, Milford Graves, Ed Bullins, Robert Macbeth and the New Lafayette family, 1968. Marvin became associate editor of Black Theatre Magazine, a publication of the New Lafayette Theatre. Much in the manner of David Walker's Appeal, one of Marvin's duties was distributing the magazine coast to coast, especially to the black colleges and universities.Harlem reception for Marvin X. He was in NYC to speak at NYU memorial for poets Jayne Cortez and Amiri Baraka. Reception was at the home of poet Rashidah Ishmaili.

Original West Oakland Nigga's fa life at Bobby Hutton/Defermery Park. Marvin says, "Growing up in West Oakland, nigga wasn't a bad word, but if you called a nigga black, you had a fight!

Angela Davis, Marvin X, Sonia Sanchez

Marvin X and oldest daughter, Nefertiti, urging her father pass the baton at Laney College BAM 50th Anniversary.

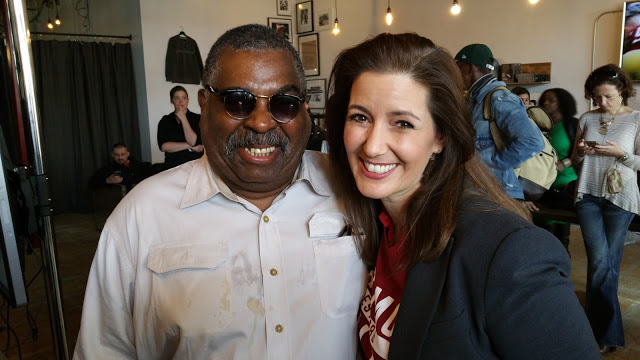

Marvin X and Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf

"Marvin X is a wonderful personality!" says the Mayor

Poet/freedom fighter Marvin X with students at the University of California, Merced, after his lecture on the Black Arts Movement and a conversation with students on his BAM classics Flowers for the Trashman and Salaam, Huey Newton, Salaam (with Ed Bullins). Professor Kim McMillan says her students love the dramatic works of Marvin X. She wishes he would write more dramas. Kim notes her students love his works and him as well. "And I love my students as well, after all, I married two of them Muslim style while teaching at Fresno State University and University of California, Berkeley. They gave me three of the most beautiful daughters any parent, especially a father, could want, Nefertiti, Muhammida and Amira!"

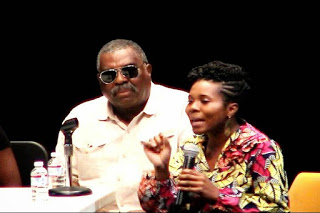

Today, Feb. 15, the indefatigable, peripatetic Black Arts Movement poet/playwright/essayist/planner/organizer, Marvin X, was interviewed by University of California, Merced, theatre students in Kim McMillan's class. They questioned the co-founder of BAM on two BAM classics: Flowers for the Trashman and Salaam, Huey Newton, Salaam (with Ed Bullins), the one-act based on his last meeting with Dr. Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, in a West Oakland Crack house. Students told the poet that some of their fellow students doubted the revolutionaries were ever on crack. Marvin X responded that some people want to maintain a romantic and idealistic notion of us in the black revolution, as though we were not human and beyond the societal forces that were oppressing us. If truth be told, all classes and sectors of our community succumbed to the US drug war to destroy our liberation. He noted that he was in jail with the President of Merritt College, who was there on drug related charges. "As my father said of myself, 'Boy, you so smart, you outsmarted yourself!'"

Marvin didn't tell the students when he produced his docudrama One Day in the Life, about his addiction and recovery, including the Huey Newton scene, the New York revolutionaries at Sista's Place in Brooklyn, told him that no excuse was acceptable for him and his comrades, Huey, Eldridge, David Hilliard, falling to Crack addiction. In Salaam, Huey Newton, Salaam, Huey tells Marvin X, "We had to experience this, Jackmon, but we can come out of it--we came out of slavery, see what'm saying?"

Marvin told the students via telephone, "Well, Huey didn't make it out, so I'm here to tell the story." In the Black Arts Movement tradition of telling the raw truth, I can't romanticize the revolution. I'm duty bound to tell the truth. For sure, we were romantic idealists thinking we could defeat the US with pistols and shotguns."

But we made an impact that reverberated around the world. Imagine, Huey P. Newton met with Chinese Premier Cho En Lie. Eldridge, Kathleen and Elaine Brown met with General Giap who defeated the US in Vietnam. They also met with the North Korean leader, Kim Ill Sung, grandfather of the present leader of North Korea. Alas, the Cleaver's son, Ahmad Cleaver, celebrated his first birthday in North Korea, hosted by the wife of Kim. She also named the Cleaver's daughter, Joju, who was born in North Korea.

Students asked about Marvin's refusal to fight in Vietnam. "Yes, I refused to be a running dog for American imperialism. I fled to Toronto, Canada, Mexico City and Belize, Central America. They deported me from Belize for being a Communist (although I was not) and a Black Power Advocate (which I was). After arresting me and the Minister of Home Affairs read my deportation order, I was taken to the police station and told to sit down in the lobby until it was time for the plane to leave for Miami, Florida. Meantime, I was soon surrounded by black police officers and when the circle was full, they asked me to teach them about black power!" After which, I was taken to the airport and literally thrown into the plane to Miami. When the plane landed, I was met by two fine gentleman representing US Marshall's office. They kindly delivered me to Dade County Jail and later to Miami City Jail and ultimately to San Francisco City Jail and Terminal Island Federal Prison.

Upcoming events in the life and times of Marvin X and the Black Arts/Black Power Revolution

March, 2018

The Oakland Museum of California will exhibit Respect Hip Hop, including the archives of Marvin X and the Black Arts Movement.

Critic James G. Spady says, "When you listen to Tupac Shakur, E-40, Two Short, Master P or any other rappers out of the Bay Area of Cali, think of Marvin X. He laid the foundation and gave us the language to express black male urban experiences in a lyrical way."

Publication of X's Notes of a North American African Artistic Freedom Fighter, essays, Black Bird Press, Oakland, 300 pages, $29.95.

Order direct from the publisher: 510-200-4164.Credit cards accepted. We have Square. Fuck Amazon! "Amazon is selling one of my books for $2,400.00 and $700.00, but I don't get a dime. I agree with the Last Poets who tell their audience, if you don't get our CDs directly from us, don't buy them cause we ain't gettin shit!"

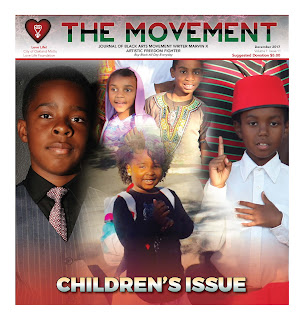

Look for The Movement Newspaper, a writer's Journal of the BAM, print and online editions. For more information, email mxjackmon@gmail.com for submissions, subscriptions and advertisement, six times annually, depending on funds. Donations accepted and appreciated. Call 510-200-4164 for more information.

Friday, February 9, 2018

Dr Lige Dailey Jr joins ancestors--celebration at geoffery inner circle, sat 11am

I am reeling from the knowledge that one of my dearest and oldest friends has passed.

If you knew Lige and his writings and poetry, you'd know we have suffered a significant loss.

A brother so full of life! He cherished, nurtured, and encouraged the best in us...individually,as family, and as community.

I will always keep him close to my heart but it hurts to think that he's no longer here to read and write to us of things that stir our spirits, hearts, and souls.

Please share this with people who knew Dr. Lige Dailey, Jr and Ardella Dailey, his wfe (40+ years) --another of my oldest and dearest friends.

Peace and Love to Ardella, their children, and her family,

Jo Ann

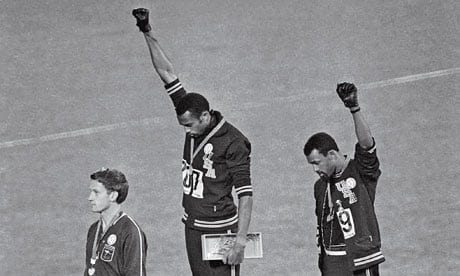

black power

| |||||||||||

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

interests and common concerns. This was something beyond what the sociologists simply characterize as "community". The Black community was virtually regarded by all of its constituents as sacred territory. The community was neither to be fouled nor abused. Without formal pronouncements, the folkways of the community established and defined the norms of behavior. The behaviors of young folks in the community suggested that they were, in fact, modeling the behaviors of the age group in front of them. Generally speaking, everyone was consciously concerned with being a good member of the community. This spirit prevailed even while we as young people did "young people's stuff".

interests and common concerns. This was something beyond what the sociologists simply characterize as "community". The Black community was virtually regarded by all of its constituents as sacred territory. The community was neither to be fouled nor abused. Without formal pronouncements, the folkways of the community established and defined the norms of behavior. The behaviors of young folks in the community suggested that they were, in fact, modeling the behaviors of the age group in front of them. Generally speaking, everyone was consciously concerned with being a good member of the community. This spirit prevailed even while we as young people did "young people's stuff".